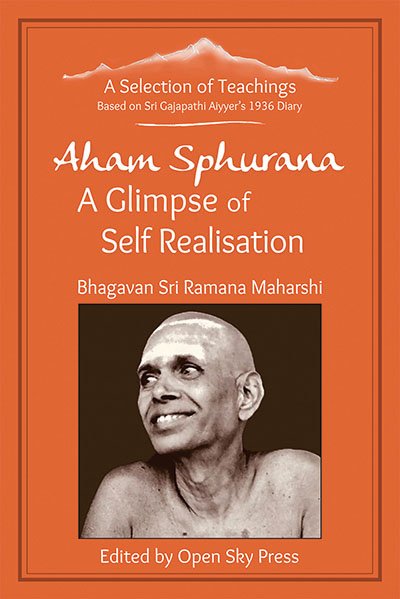

Aham Sphurana

A Glimpse of Self Realisation

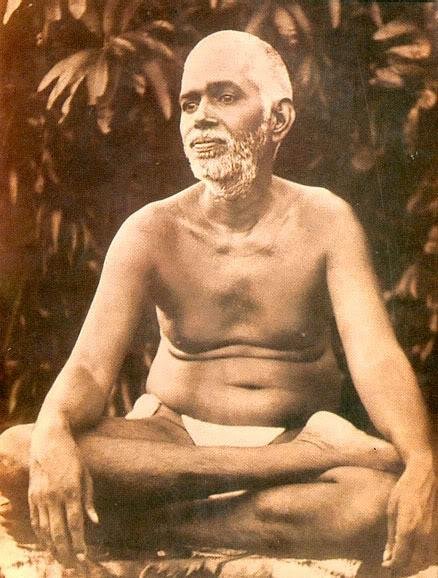

New Book about Sri Ramana Maharshi

Available Worldwide

On www.openskypress.com and Amazon:

“In my opinion, Aham Sphurana, a Glimpse of Self Realisation, will become a Treasure Trove of Wisdom to the Seekers of Truth in general, and particularly to the devotees of Bhagavan.”

Swami Hamsananda – Athithi Ashram, Tiruvannamalai

Sri Gajapathi Aiyyer Ashram Report

9th September, 1936

For the most part of today I was unable to go to the Ashram. Since Sri Cycle-Pillai seemed to be indisposed for the time-being with one of his occasional abdominal ailments, and was thus not in a position to do his usual chores for the Ashram, the sarvadhikari [manager] has asked me to purchase roots of the shathavari [Asparagus racemosus] plant from a herb dealer who put up his wares in different parts of the town on different days.

The sarvadhikari gave me three annas; this meant I was to purchase three annas worth of roots and take them back to the Ashram as soon as possible. I was not inordinately delighted with the chore, but still agreed to do it because I knew who it was for. I had been given the task because the herb dealer sometimes spread out his wares at the entrance of the street where I was put up. But today he was not there; everyday he went and squatted at a different place, spreading out his condiments before him on a piece of khaki-coloured canvas.

He himself would not sit on the canvas; I know not why; he would unwind the raggedly towel around his head, spread it on the floor, and seat himself on it; at the end of the day, the towel would be back on the head, and he would gather up his inexpensive wares in a little brown bundle, and carry it away in the crook of his arm, fondly hugging it to himself as if the thing were his new-born baby. He would invariably leave when the sun’s light began to fade; perhaps he could not afford a kerosene lamp. After making inquiries, I finally found him today near the Ammani Ammal gopuram, bought the necessary item, and made haste to return to the Ashram.

The sun was not merciful, but the fact notwithstanding I walked to the Ashram because I did not like to haggle with the town’s contemptuous tongawalas [horse and cart taxi]. All along the way my thoughts were with poor Major Chadwick, for whose sake this purchase had been made. He had been suffering for the past few days from an acute and relentless attack of dysentery, forcing him to keep away from the Hall and stay amidst vegetation on the distant slopes of the Hill.

Bhagavan noticed his unusual absence from the Hall and sent for him. Feeling sorry for his plight, a gentleman known as Lakshmanan, a Congress worker from Pondicherry and a devotee of the master, has volunteered to take care of him. The gentleman is apparently an ace at practising Ayurvedic remedies. He told the master that he had the other ingredients but needed just one more: shathavari roots. The task was assigned to me. Evidently, since I am neither eating nor sleeping at the Ashram, the sarvadhikari did not relish giving me work; but consequent to the fact that I sincerely felt sorry for Chadwick, I agreed to help him by fetching the roots.

As I walked towards the Ashram my thoughts were with Chadwick. He was a war veteran from the Great War. He could lead a comfortable life in England. Yet he had opted to mortify himself in this manner, all for his love of the master. I wondered if I had been born as a Caucasian and were to be in the retired Major’s position, would I still be interested in Bhagavan — probably not, I thought to myself, for I must be honest in my self-appraisal. I would read books by and about him, certainly. But personally come and stay here and get attacked by dysentery? No.

The Major — did he feel bored here? It was a question that sometimes popped into my head whilst I set eyes upon his towering frame. He did not have many friends here — five at present, at most. Bhagavan, S. S. Cohen, Bhagavan’s rudraksha-adorned attendant, Mr. TKS, and myself. Was it proper to include the master in this list, since his State was Transcendental and thus did not permit him to see anybody as an “other”? I do not know, but certainly the master was more than a friend to Chadwick. One did not leave England and come to some corner of an unknown land in order to be in the vicinity of a mere “friend”. How much joy did Bhagavan’s presence fill him with? Evidently exceedingly a great deal because he had never turned back and left.

The surprising thing was that even before he had met Bhagavan he had decided that he would stay with him till the end; in other words, at the time of leaving England he had been determined to leave Her for good! And what about his other friends? The rudraksha-adorned attendant, he told me, was an extraordinary fellow. Although his actual name was something else, the master called him Annamalai the moment he set his eyes on him and so this was his name at the Ashram. Since he is executing more than one construction project here, I assumed he was a professional engineer who had come to serve Bhagavan, but Chadwick astonished me by saying that he had never been to school.

Chadwick had also brought me up to date with many other fascinating details pertaining to this man’s life, which he knew owing to the fact that they were staunch friends. He had come to the Ashram a decade back and had been assigned to work as Bhagavan’s attendant. In a week or so, he had grown tired of his role and had left, but poverty had forced him to return. He came back to the Ashram and clasped hold of the master’s feet in a gesture of solicitation of pardon, since he had discourteously left without telling anybody.

The moment he made contact with Bhagavan’s flesh, he heard the sound of a bell ringing followed by the master’s voice reciting a shloka. Both the sound of the bell and the sound of this shloka being chanted in the master’s voice were, peculiarly enough, heard by him inside his body, and the same were not heard by anybody else among those who were at the time present in the Hall. Also, at that very moment, owing no doubt to Bhagavan’s Grace, memories of his previous lives returned to him.

In his previous life he had been Mr. William Talman, the great English architect who had single-handedly rebuilt much of that country after it stood thoroughly mangled by the great fire that totally conflagrated it during the 17th century. Yet while he remembered all his previous architectural knowledge, he could not recall how to speak the English tongue. The master smiled at him and told him that henceforth, he should take care of all the building works at the Ashram. Mr. Talman — that is to say Annamalai Swami — agreed eagerly. Although in fact on that day he had ceased to serve as the master’s attendant, he did not relinquish the post altogether. He helped the master by rubbing oil all over his body whenever the latter needed to take anointment with an oil bath.

Mr. Talman being a fellow Englishman and fellow devotee of Bhagavan, I thought it was natural that immense affinity should develop betwixt the soldier and the architect. They even shared the same room. It had happened thus: when Chadwick had moved into the Ashram, the sarvadhikari had asked Annamalai Swami to vacate his room so that the towering Caucasian should exclusively be able to stay in it. Although the architect-attendant immediately endeavoured to comply, the kind-hearted Major did not wish to see another inconvenienced for the sake of an increase in his own comfort. So, to the surprise of one and all, he summarily announced that he would have no objections in sharing the room with Annamalai Swami.

For some reason, Chadwick said, Bhagavan had never permitted this architect-attendant to spend any time in the Hall, even before the massive construction projectscurrently going on in the Ashram had begun. This has been my observation also. As soon as he entered, he would be sent out on a fresh building assignment, or to the care of some structure that stood out as being in need of repairs. My own surmise is that his desire during his lifetime as the original Mr. Talman to construct buildings for God Himself is being played out in this life. Bhagavan wants his desires to fulfil themselves fully so that there can be no more birth for him; thus he keeps him busily engaged in construction work all the time so that this desire can be exhausted sooner and he can expedite attainment of Moksha.

Chadwick has remarked to me more than once, “I wonder whether Annamalai Swami regrets the fact that he is unable to spend as much time in the Hall with the master as a regular attendant would be able to.” This remark on the Major’s part betrays how deeply sensitive his nature is, though he seems casual and carefree on the outside. He puts himself in the shoes of another and then wonders about that person’s problems from his perspective! The Major had once rescued Annamalai Swami from a grave crisis.

More than a year back, a group of devotees constituting the Ashram’s agglomeration of managing committees had decided that Annamalai Swami was to be regarded as being a villain because he was wasting the funds of the Ashram by unnecessarily constructing grandiose buildings that in their opinion the Ashram would never feel the need for. They asked him to stop all his construction work and surrender his responsibilities to them. Henceforth, they said, he would have to be content with being the master’s attendant. Annamalai Swami flatly refused.

The irate group asked him on whose authority he was putting up buildings left, right and centre inside the Ashram premises. Annamalai Swami replied that he was acting on his own authority. The gentlemen constituting the group secretly conferred amongst themselves and decided that the police must be called in the middle of the night to have Annamalai Swami ejected from the Ashram. The actual fact was that Annamalai Swami was putting up the many buildings he was constructing here only because Bhagavan had privately asked him to. Moreover the master had told him that he must never disclose the fact that he was acting under his orders, but must always pretend that he was acting of his own independent volition.

Annamalai Swami told nobody, but Chadwick had guessed that he would not be engaging himself so strenuously were not the master’s orders behind it all. He asked him if that were not so. On being confronted with the question from his dear friend, Annamalai Swami laughingly admitted that the Major’s surmise had been correct. Now, the group discreetly contacted Chadwick and told him not to be surprised if a policeman knocked on the door of his cottage in the middle of the following night. Chadwick asked for the reason and was horrified when informed of it.

He told the group that the entire idea of putting up so many elaborate buildings one after the other on the Ashram premises was Bhagavan’s. The gentlemen were initially sceptical but later, in a dilemma as to whether to believe the earnest-sounding Major or not, asked Annamalai Swami if it were not so. Annamalai Swami, not one to break a promise of confidentiality he had made to the master, stubbornly maintained that he was doing everything solely of his own accord. The group then went to Bhagavan himself in order to get matters clarified.

But Bhagavan would not even look in their direction. Chadwick arrived in the Hall at that moment and said to the master agitatedly, “They are planning to forcibly evict Annamalai Swami from the Ashram.” That very moment the Maharshi thundered in an uncharacteristically booming voice, “The moment Annamalai Swami is forced to leave the Ashram, I will also go away.” The group, upon hearing these words, went away quietly and never made any further attempt to disturb the construction work going on in the Ashram, realising that it was indeed the master who must have issued orders for all these works to be carried out.

Soon after, it had become common knowledge in the Ashram that Annamalai Swami was merely carrying out Bhagawan’s orders in executing all his elaborate building projects. Thereafter nobody dared to comment on how resources were being wasted in putting up huge buildings when smaller ones would suffice.

Chadwick had told me of all these little interesting incidents, and more, whilst I sometimes visited him during the late evenings in his little cottage, which he happily shared with Annamalai Swami during the night. Some of his other anecdotal rambles I recollect were:

(a) When the Major had first arrived in the Ashram, he had prostrated in front of Annamalai Swami, imagining that the latter was Bhagavan!

(b) Soon after Chadwick moved into the Ashram, a letter addressed to the master arrived from one Arunachala Mudaliar living in town. It carried the baseless complaint that Chadwick was regularly and clandestinely purchasing beef and secretly roasting or barbecuing it on a fire he lit every Sunday near Palakoththu, and everyday consuming it inside the Ashram precincts, whilst silently sitting next to Bhagavan’s mother’s Samâdhi. The letter was also signed by one Gopal Rao, a former manager of the Ashram!

(c) Bhagavan once told the story of how in the early days of the Ashram there was a big fight between one Dhandapani Swami, a former manager of the Ashram, and the sarvadhikari. Dhandapani Swami became excessively enraged and tried to push the sarvadhikari into the Agatthiyar Theertham. The sarvadhikari would have drowned if the master had not scooped up from the ground some cow-turd and flung the same squarely at Dhandapani Swami’s face. The humiliated Dhandapani Swami stopped fighting at once. Bhagavan had then explained to one and all present there that his intention was not to insult Dhandapani Swami, but only to ensure that sannyasis in general did not acquire a disreputable or reprehensible name.

With these and other thoughts roaming around inside my head, I entered the Hall and prostrated to the master as usual. Then I told him that I had procured the required roots. The master acknowledged the fact with a smile and stretched out his hand for the condiment. He held it close to his face, smelled it carefully from various angles, remarked, “It is of marvellous quality — thoroughly dried, with no fungus infestation; good,” and handed it over to me so that I could give it to the sarvadhikari, which I then did. “It is precisely for three annas — is that not so?” he said good-humouredly. “Good fellow! See how much he has given us for three annas.” I was then asked to hand it over to Mr. Lakshmanan. I went to the cow-shed, where I was told he could be found.

He was tending to a sick cow, administering to the uncertain, reluctant animal a frothing and foaming herbal decoction. It was attempting to withdraw its head away from the bucket into which the man was pushing it, coaxing it to drink what I guessed would be some not-delicious substance of his own contrivance and manufacture. I was asked to hold the unfortunate animal’s snout, which I did. Mr. Lakshmanan fastened a rope around the cow’s head, and her mouth was now confined to the bucket. “This is what we must do with the rebellious mind,” he remarked to me grimly as I handed over the roots to him. But the moment he finished saying it, the cow violently tilted her head, and most of the mixture splashed out of the bucket.

We heard a familiar laugh, and it was Bhagavan! He caressed the cow gently and she relaxed her mouth into the bucket. He waited for a minute. Then he took the rope off, but the cow made no attempt to extract her mouth from the bucket. “No, this is what we must do with the mind,” he said, and Mr. Lakshmanan smiled feebly. I laughed. Then we went back to the Hall.

At that precise moment a gigantic distraction entered the Hall and rushed straight at the master. It was a hefty youth wearing nothing but a slender loin-cloth and brandishing a thick bamboo stick. Before anybody could even think of doing anything to thwart him, he sat next to Bhagavan on the Sofa, put his arm over the master’s shoulder, shook him vigorously, and screamed out aloud, “We are both Jnanis, worship us, you silly morons!”

One of the attendants said ruefully, “Oh! It is you again!” Both attendants rushed out of the Hall and in less than a minute returned with Annamalai Swami. “Oh! You have returned!” said the youth to the architect-attendant. “Those are the words I am supposed to be saying to you!” exclaimed Annamalai Swami with a laugh. Then there began a tug-of-war. The attendants caught hold of the man’s stick, which he seemed reluctant to let go of. Using their hold on the stick, they dragged him to the entrance, threw him out, and shut the door. Since he was holding the Sofa with the other hand, the Sofa, together with Bhagavan on it, also moved automatically near the door.

Bhagavan, who had been impeccably serene all this while, got up with a laugh and the Sofa was moved back to its place in the Hall. But the man was now spitting through the window; so all the windows, too, were closed and we sat there in semi-darkness. They were opened again only after forty-five minutes! Cohen asked Bhagavan, “Has this man already come here?”

B.; [laughs] Yes! He has got the idea that he is also a Jnani, but that nobody is respecting him or worshipping him. So, he is coming and sitting here so that his ego may feel appeased.

What can we do? Can we say it is wrong? In the absence of the distractive, sleepy and nebulous phenomenon known as mind, all are truly Jnanis.

Edited by John David Oct 2021