Aham Sphurana

A Glimpse of Self Realisation

New Book about Sri Ramana Maharshi

Available Worldwide

On www.openskypress.com and Amazon:

“In my opinion, Aham Sphurana, a Glimpse of Self Realisation, will become a Treasure Trove of Wisdom to the Seekers of Truth in general, and particularly to the devotees of Bhagavan.”

Swami Hamsananda – Athithi Ashram, Tiruvannamalai

Mrs. Piggot Introduces the Ashram

And Bhagavan’s Meetings in 1934

4th September, 1936

I had visited India on several occasions prior to this trip, but this was

my maiden venture off the beaten track.

I was told of Sri Ramana Maharshi, and even from the little I heard, I knew I would travel anywhere and put up with any inconvenience in order to meet him and experience the sanctity of his presence. The friend who gave me the welcome news of the Maharshi’s existence offered to take me to him, and so we arrived at Tiruvannamalai late one afternoon.

Dakshinamurti Shrine

On the way to the Maharshi’s ashram, it is observed by me that our vehicle passes a simple stone- shrine which stands dedicated to Siva as Dakshinamurti, the most ancient of Yogis who teaches the Ineffable Absolute Truth through Silence of the Soul. He is a deity who perpetually faces south, and consequent to the fact that south is the direction of death, He is also known as Mrutyunjaya, the Conqueror of Death. Death, indubitably, is conquered by awakening to the ultimate truth of ourselves.

Just after passing the shrine of Dakshinamurti we reached our destination, announced by an archway bearing the words ‘Sri Ramanasramam’. Having entered the grounds we dismounted from our vehicle. The Maharshi’s younger brother Sri Nagasundaram greeted us there. He was the Ashram manager known as the sarvadhikari or as Chinnaswami.

Meeting Bhagavan

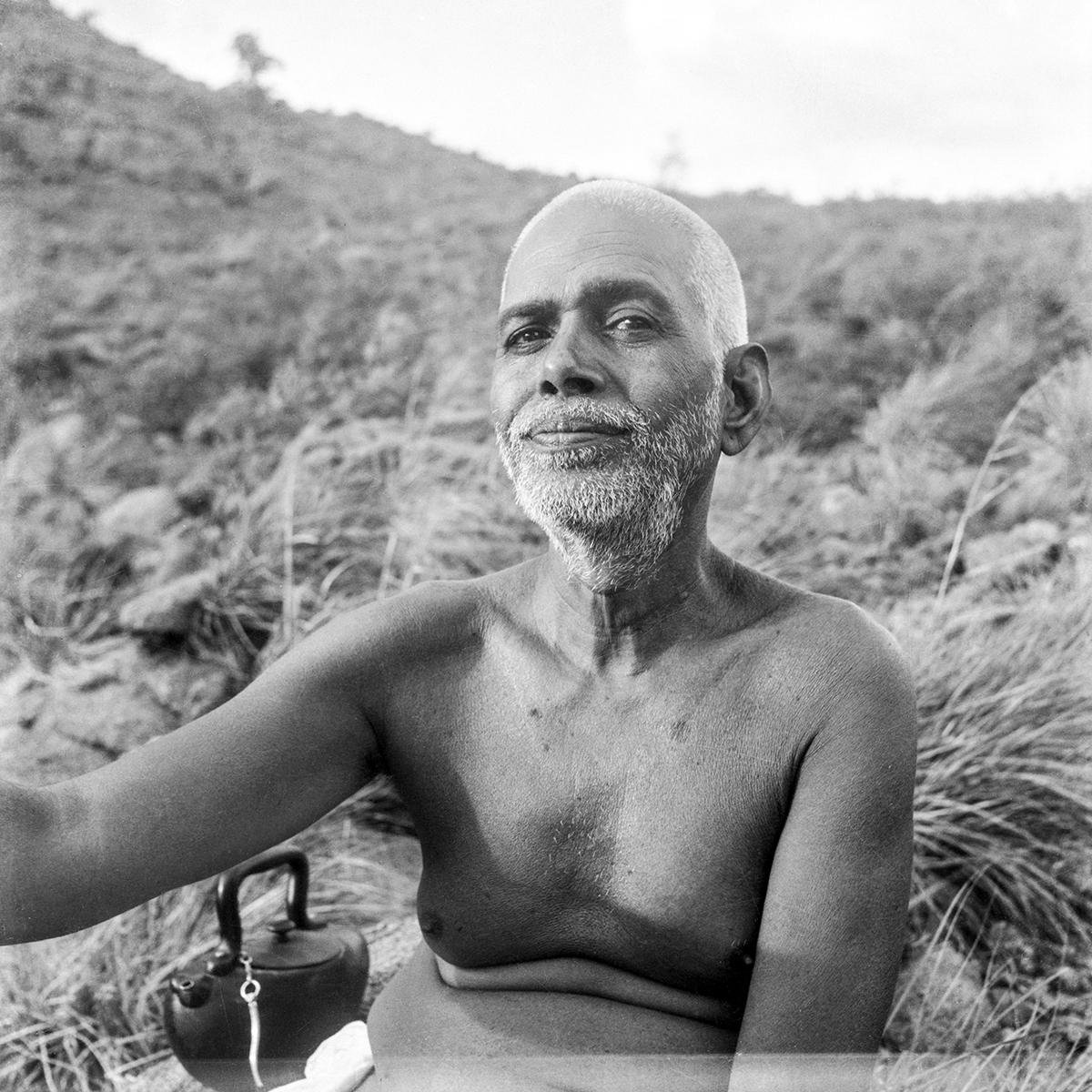

He informed me that I could now have Bhagavan’s darshan. I crossed a small courtyard and came to a long hall with all its doors and windows open. I went up a few steps and there, seated before them on a couch, was the Sage of Arunachala. He is a slender, golden-skinned man in his late fifties. Except for a loincloth, he is completely nude.

In front of the couch sandal-sticks were burning and a small brazier of hot-coals, on which a special kind of incense was constantly being thrown. Although born a brahmin, Bhagavan’s features actually made him look like a docile country-side peasant. However, the awareness of the Absolute is marked out clearly on the face, making it profoundly serene and beautiful.

The splendour of Realization is clearly evident from one look at his face. I now see that the psychological labels which the modern mind tended to affix to spiritual-experience turn out to be irrelevant and unworthy when one is confronted with true achievement.

I was so engrossed in my contemplation of Bhagavan that at first I did not hear when one of the attendants told me that I should take my place among the women, who sat on the master’s left. The men, who were more numerous, sat facing him down the length of the Hall.

The Hall in which the attendees found themselves was simply decorated andfurnished. A frieze of blue flowers ran along the walls. A clock hung on the wall facing the devotees. Below it, on a shelf, there were a few tin containers. Presently, I saw Bhagavan take some nuts out of one of the containers for the squirrel that had run to him along the back of the couch.

Yet the banal setting could not detract from the grandeur of the Sage. He was exceptional first of all in just being himself. In every action he made, whether he was correcting a manuscript or reading a letter, there was a complete naturalness and absence of pose. This is veryrarely seen, for few are those who, being rooted in their true identity, have no need to seek a flattering image of themselves or confirmation of what they are from the impression they make on others.

Lunch

At 11 hours Bhagavan and the devotees rose and left the Hall, for it was time for the main meal of the day. The meal was served in the communal dining hall where rows of freshly washed plantain leaves had been laid out on the spotlessly clean stone floor. Bhagavan took his place among the devotees. The brahmins sat on one side of him and the non-brahmins on the other, thus respecting religious customs. Bhagavan, though, did not wear the brahmins’ sacred- thread, and I remembered that on arriving in Tiruvannamalai he had thrown away the thread worn by the hereditary, sacerdotal race that indicated superiority over every other race.

I was served rice, vegetables, pepper-water and milk-curds. Bhagavan ate veryfrugally. He asked me courteously whether the food was not too pungent for me. These words of solicitude were the first words he spoke to me.

Hall Meeting

In the Hall I then joined the devotees who had come to spend the afternoon with Bhagavan. I did not see some of those who had been present in the morning, but several newcomers were there. I was surprised to hear that devotees might come into the Hallas early as four o’clock in the morning, though seven o’clock was the time most morning visitors gathered. Many spent only a few hours with him, but he was accessible to visitors all day long. As in the morning, the mood was rather informal. To those pupils aspiring to attain the highest grade of knowledge, Bhagavan apparently did not give any discourses. He replied to questions when they were put to him, usually very succinctly, as if to let the one word or the few words he said make their way directly into the understanding of the questioner.

On the other hand, when a young man struggled to grasp what the Absolute Self was, Bhagavan with great patience guided him through his reasoning until at last he got some glimmering of what Bhagavan meant. Of course, the answer to the nature of the Impersonal Noumenon is only to be found on the intuitive level, but the breakthrough of intuition can be hampered by faulty reasoning. Apart from these exceptions to silence, there were long quiet moments when Bhagavan said and did nothing, but which were more effective in conveying transcendent Truth than any lecture orsermon would have been.

Coffee and the Evening Meeting

The afternoon ended with a twenty-minute break for the purpose of taking coffee, and presently Bhagavan got up and went for his evening walk. This was the signal for ageneral exodus, and we all trooped outside.

Bhagavan and the devotees gathered in the Hall again at five o’clock for the evening session. I found that the atmosphere now was quite different; much more solemn and charged with more energy than earlier on in the day. First there was the recitation of the Vedas by a group of young brahmin boys and their preceptor. As the powerful Sanskrit syllables vibrated in the Hall, Bhagavan’s appearance underwent aremarkable change. His expression became austere, his gaze turned inwards. His face appeared translucent as if lit by inner illumination, whilst the constant slight trembling of his body which I had noticed earlier, had now completely stopped.

Yet even in this state it was evident that he was not oblivious of his surroundings, and that he had an awareness of both the inner and outer reality. After the Vedas, the devotees sang together a hymn to Arunachala. Then they sat in deep silence, capturing the force emanating from the master, a force so strong as to be almost tangible. Bhagavan’s ashram is a place where exclusively those people who have dedicated their entire lives to the spiritual quest may take up permanent residence.

Often there are no orders or binding rules, and anyone can come and go as he pleases. I discover to my pleasant surprise that most of the people living in the ashram speak English and are eager to greet me in a warm and friendly manner. On the day of my arrival, more than a dozen people tried to strike up a conversation with me. In their accented English, they wanted well-meaningly to know how I had heard of the Master and what brought me here.

A Dialogue with the Master

It was now several hours past the time night had fallen upon the little town. The occupants of the Hall spoke in low tones to one another, and a child prattled to his mother; but soon these sounds ceased and there was quiet. I sat cross-legged on the floor with the others, though a chair had been thoughtfully provided for me.

I asked the Maharshi in a respectful hushed tone: “Thoughts cease suddenly, then ‘I-I’ rises up as suddenly and continues. It is only in the feeling and not in the intellect. Can it be right?” He was gracious enough to respond to me, saying that it was certainly right. Thereafter I tried gazing into his eyes. I repeatedly tried to capture his gaze. For a while nothing happened. I tried to concentrate my mind on the beingness of the formless Self.

Suddenly I became conscious that Bhagavan’s eyes were fixed on me. They seemed, literally, like burning coals of fire piercing through one. They glittered in the dim light of the charcoal brazier burning by the side of the Sofa. Never before had I experienced anything so devastating– in fact, it was almost frightening. What I went through in that terrible half-hour, in a way of self-condemnation and scorn for the pettiness of my own life, would be difficult to describe.

Not that he criticized, even in silence – of that he was incapable – but in the light of perfection all imperfections are revealed. To place on record how little responsible he was for my feelings, I must mention here that he told me later on that doubting, self-distrust, and self-depreciation are some of the greatest hindrances to the Realization of the Reality.

This is a record of the further conversations I had with him on the day subsequent to the one of my first arrival at the ashram:

Q.: Is a Realised Master necessary for realisation?

B.: Realisation is the result of Guru’s Grace more than teachings, lectures, meditation, etc. They are only secondary aids, whereas the former is the primary and the essential cause.

Then Bhagavan ordered a certain treatise to be read out in the Hall, in which it was stated that as in all physical and intellectual training a teacher or instructor is sought, so in matters spiritual the same principle holds good.

The master added that it was hard for a man to arrive at the goal without the aid of a Realised Master.

Q.: Yet I have heard it said that you had no Guru.

A rustle of shocked horror ran through the Hall because I had inadvertantly addressed him in the second person instead of referring to him as ‘Bhagavan’. Yet the Maharshi was not in the least disturbed or offended. On the contrary, he looked at me with atwinkle in his eye. Then he threw back his head and gave a joyous, wholehearted laugh. It endeared him to me as nothing else could. A saint who can turn the laugh against himself is a saint indeed. Ultimately he did give a response to my impertinent remark:

B.: Yes; but in the majority of cases, Guru is certainly necessary.

Q.: How shall I find the Guru?

B.: Intense meditation will impel you into the field of his presence automatically.

The Ashram

On the third day of my visit, one of the devotees offered to show me around the ashram, a cluster of small whitewashed buildings and

huts, all spotlessly clean, and joined together in some cases by a covered passageway. The ashram was picturesquely situated halfway up the famous holy mountain of Arunachala. It was on this mountain side that Bhagavan took up his abode more than thirty years ago, and ever since then it has been his home.

He must be aged about fifty years, but looks older, owing no doubt to theprivations and austerities practiced in early life. It was dark when I returned for the evening meditation, and most of the people not living permanently in the ashram had left. The Hall was compellingly still. The eyes of the holy one blazed no more. They were serene and introverted. All my troubles seemed smoothed out and difficulties melted away. Nothing that we of the world called important mattered. Time was forgotten. Life in its many aspects was now one.

Edited by John David Oct 2021