Blog

Spiritual Teachings

from the Heart of Satsang

Browse by Topic through the Archive

Or use the Search Function

Latest Blog

Love Is

The End of all Wisdom

is Love, Love, Love.

- Ramana Maharshi

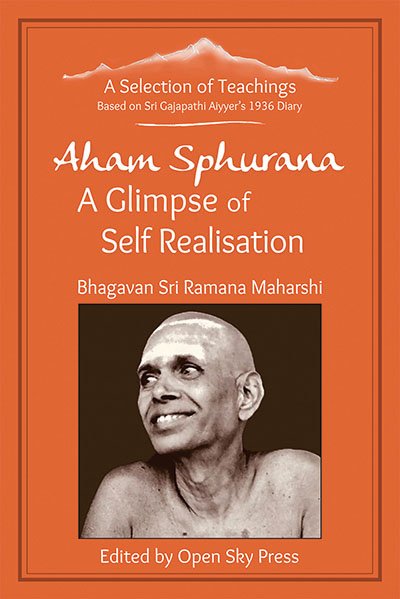

Aham Sphurana

A Glimpse of Self Realisation

New Book about Sri Ramana Maharshi

Available Worldwide

On www.openskypress.com and Amazon:

“In my opinion, Aham Sphurana, a Glimpse of Self Realisation, will become a Treasure Trove of Wisdom to the Seekers of Truth in general, and particularly to the devotees of Bhagavan.”

Swami Hamsananda – Athithi Ashram, Tiruvannamalai

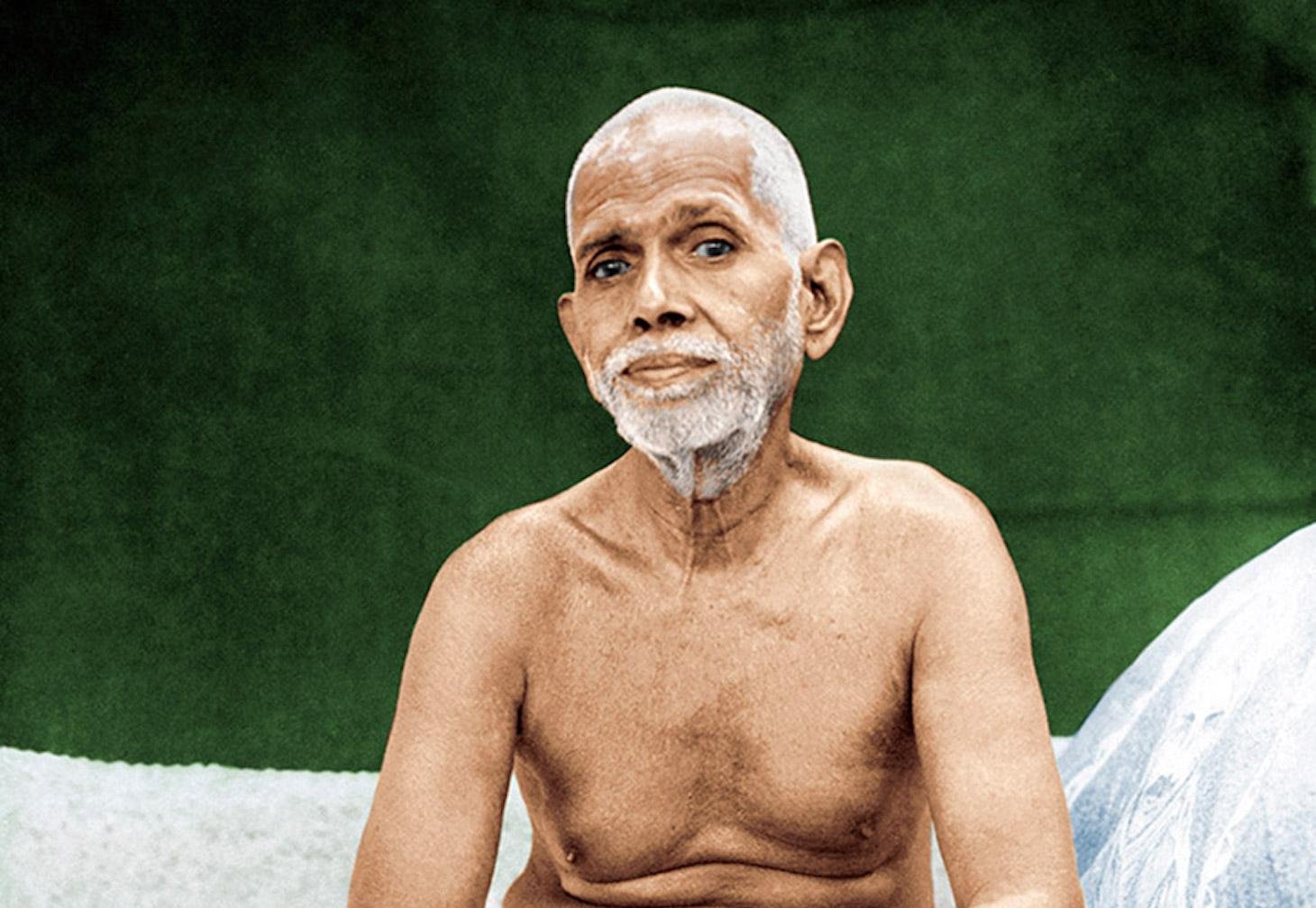

Ramana Maharshi on Love

23rd August, 1936

Today morning when I entered the Hall, Sri Bhagavan smiled at me sweetly, like a child, and handed unto me a letter, saying,

‘ உனக்கு இது பிடிக்கும் , பாரேன் !. ’ [‘See, you will like this!’]

Piqued, I unfolded it and read it. It was from a Mons. Alfred E. Sorensen [Sunyata], and ran thus [reproduced from memory] —

Oh! Master of the Formidable Mountain! I was earlier like a filthy pig, consuming with eager relish the turds excreted by the sensory organs. I came with a restless mind to impudently scrutinise your authenticity, but the moment your eyes fell on me, I became motionless like you, for you graciously annihilated my maleficent faculty of assertion-manufacture, which arrogantly declared “I”, and immersed me in my own intrinsic inner state of Absolute Being, which in truth is only You.

I kiss the dust of your sacred feet every day, for by drowning me once and for all in the unfathomable ocean of exultation which is truly You, you have devoured my traitorous mind forever. Now I live only as Love-of-you. I have happily lost myself in You, who are Love Itself. Never ever will the miseries of the world manage to trace me out again, for I see only Lovely you in them.

When your omniscient eyes bored into mine and said ‘THERE IS NO ANYTHING,’ my Heart tugged from within, and, knowing it was you who was calling, I meekly followed. There I was rendered NAUGHT; now I am NOT. Now I roam around the universe like an unbridled wild animal, knowing not what I am doing nor why. Now all I know is you in which there is no me.

My Master has been kind enough to send word through Mr. Hurst that he regards me as a Sahajajnâni, or natural mystic. But my joy is in knowing that this ugly form — which I once considered as one with myself — has found a place in my hallowed Master’s memory! Although now there is no question of anything remaining apart from my Master, my heart aches to set eyes upon his physical frame again. May Sri Bhagavan expeditiously fulfil my wish! [Leave-taking:] Bhagavan’s Love

G.: Who is this man?

B.: He came here earlier this year, perhaps at Mr. Brunton’s invitation.

G.: Bhagavan took one look at him, and he attained the Final State?!

B.: [twinkling] Bhagavan does not cause anything to happen. Why, are you thinking along the lines of “Oh! I am sitting in the Hall every day, hearing reports of people obtaining lofty, transformative, spiritual experiences from Bhagavan every day, and avidly listening to Bhagavan’s teachings every day — when is all this going to bear fruit, and when shall I become a Jnani? Is the allure of Jnana sorely tempting you?!” [laughs]

G.: Oh! no. The moment I came here and Bhagavan looked at me, I forgot all about myself. Now I think only of Bhagavan, who is already a Jnani. So, for whom am I to ask Jnana?

B.: The secret of Jnana is bhakti. Unselfish Love — motiveless, incessant, intransigent Love — is the key that unlocks the Gate of the Heart once and for all. Long and yearn for Him fervently not so that He may destroy your ignorance, but merely because such Love is possible [unto you]. One alone who knows so to madly Love has fulfilled the purpose of human birth; he need not be born again. The Loveless ones repeatedly come back to the fetid ocean of samsara to suffer more and more.

G.: To everyone who comes here Bhagavan recommends vichara only.

B.: Vichara is a means to eliminate ignorance, which obscures Love from Shining forth — for the nature of the Self is Love Itself. Love cannot be practised as a sadhana. All that is possible is to surrender to it. There is no such thing as inculcation of Love.

Love is already there. It alone IS. All that is needed on your part is to give up thought, which makes you imagine yourself to be apart from Love, and so merge in Love. Then there is only Love, which is bliss beyond imagination. To one who has discovered the ecstatic joy of volitionless Love, sadhana is a laughable absurdity. To those who solicit justifications, we may say that such Love blossoms only in souls which have perfected their sadhanas in previous births.

G.: But among sadhanas [ practices] vichara is the best?

B.: Undoubtedly.

Edited by John David Oct 2021

Letters to Bhagavan

Aham Sphurana

A Glimpse of Self Realisation

New Book about Sri Ramana Maharshi

Available Worldwide

On www.openskypress.com and Amazon:

“In my opinion, Aham Sphurana, a Glimpse of Self Realisation, will become a Treasure Trove of Wisdom to the Seekers of Truth in general, and particularly to the devotees of Bhagavan.”

Swami Hamsananda – Athithi Ashram, Tiruvannamalai

Letters to Bhagavan

During the Master’s lifetime, the practise existed in the Ashram for devotees to send in letters asking for all manners and varieties of things. Most begged for Bhagavan’s blessings in their endeavours, and specifically would mention that the sheet carrying the reply be sanctified by his hallowed touch.

Many wrote wanting their prayers or wishes to be fulfilled. Others solicited clarification on doctrinal points. Yet other epistles carried doubts raised regarding practice. Sri Bhagavan was not in the habit of answering letters. An intelligent brahmin attached to the Ashram was in the habit of attending to the last two varieties of correspondence. Invariably most, letters written in European tongues would fall into his hands to be tackled appropriately. He would write and read out his replies to the Master.

When I was maintaining these diaries, I would write them down after a natural, syndicated fashion; thus in this manuscript, you behold amalgamated and mingled the content of these letters together with questions asked directly in the Hall. This need not be understood as causing any detriment in the authenticity of the content of these diaries. While it is true that the replies were drafted by another, the master listened to them with great keenness, and if he wanted any modifications, deletions, or additions to be made, he indicated so at once.

He did not mind delivering a rap on the knuckles to the man should Bhagavan in the slightest feel that there was any correction or other alteration required to be made. So, in substance, the answers given in the letters are also his words. Thus at the time of writing these diaries it never occurred to me to create a split on the basis of what would merely be a theoretical consideration exclusively. Now, whilst compiling this work, it occurs to me suddenly that certain readers might be anxious for such a bifurcation to be available from the text.

I have neither the resource nor the resourcefulness to re-type this manuscript ab initio; thus I have resorted to the following strategy: as to that part of this manuscript which falls on or before this date [of the diary-entry], a separate sheet has been attached specifying the identification-numbers of those pages and paragraphs which embody content that – to the best of my memory – represents the master’s ‘indirect words’, if one may so put it; and as to that part thereof which falls after, I am using an alternate type-basket of the font-variety Clarendon to mark out, as facilitated to be determined by an optimal capability of the faculty of my memory, distinctly such ‘indirect words’, whereas the rest of the matter is typed out as usual in the font-variety Frakturschrift.

Generally, a sizeable portion of long, lecture-like pronouncements herein are from the brahmin who was at the time in charge of the “doctrinal- and foreign-correspondence departments” of the Ashram. In truth, I am taking so much trouble to make this bifurcation discernible, only to satisfy a chance whim of any Ramana-devotee who might happen to have to be able to tell. Actually it is all thoroughly unnecessary, as far as my opinion goes; not a single letter could leave the Ashram without the master’s express imprimatur; and the master was not the sort to show neglect in any matter.

The brahmin was quite an educated fellow and had a brilliant insight into Bhagavan’s teachings, and frequently acted as his interpreter unto Caucasian visitors. Above all, he seems to have been personally selected by the master himself for the correspondence-management task in the doing of which he engaged himself; that ought to say the final word upon the matter.

BLUTKEIM’s Note: What you are reading is the content of text files – to be exact, .wsd files generated by WordStar, which had to be converted into text files so that they could be made intelligible to modern-day word processors. There is no font information available with me. No trace was found of the separate identification sheet mentioned above.

Edited by John David Oct 2021

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.