Blog

Spiritual Teachings

from the Heart of Satsang

Browse by Topic through the Archive

Or use the Search Function

Latest Blog

A Typical Western Visitor’s In-Depth Dialogue with Bhagavan

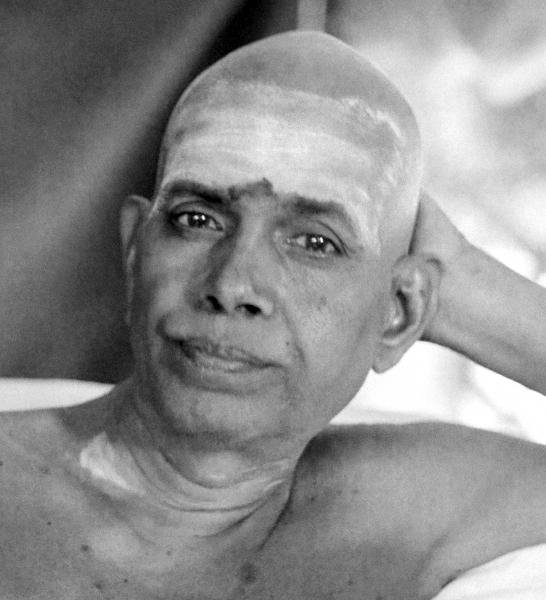

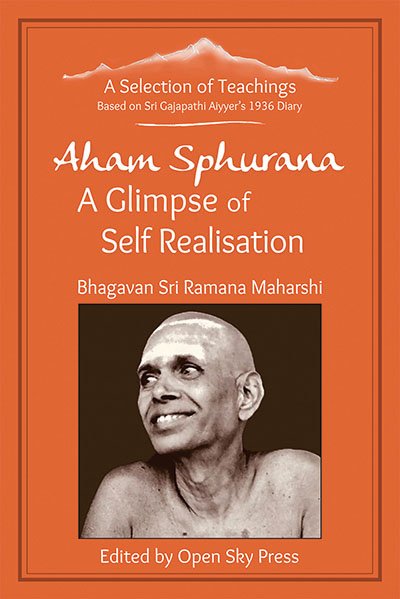

Aham Sphurana

A Glimpse of Self Realisation

New Book about Sri Ramana Maharshi

Available Worldwide

On www.openskypress.com and Amazon:

“In my opinion, Aham Sphurana, a Glimpse of Self Realisation, will become a Treasure Trove of Wisdom to the Seekers of Truth in general, and particularly to the devotees of Bhagavan.”

Swami Hamsananda – Athithi Ashram, Tiruvannamalai

A Typical Western Visitor’s

In-Depth Dialogue with Bhagavan

Time and again I have observed that the Maharshi emphasises that Realisation was more the result of Guru’s Grace rather than anything else. I had been in despair of ever again getting the Maharshi alone. It is hard to unburden the soul before a crowd.

One morning I resolutely made my way into the Hall a few hours earlier than usualand found him there unattended, emanating his usual wonderful stillness and ineffable peace. I asked quietly if I might talk with him. He nodded, smiling, and sent for someone to translate. On the arrival of a devotee, I put my first question.

Q: What are the obstacles which hinder Realisation of the Self?

B.: They are habits of mind (vasanas).

Q: How to overcome these mental habits?

B.: By Realising the Self.

Q: That is a vicious circle.

B.: It is the mind which brings about such difficulties, creating obstacles and then suffering from the perplexity of apparent paradoxes. Find out who makes the enquiries and the Self will be found.

Q: What are the aids for Realisation?

B.: Introversion of mind is the one and only aid.

Q.: How can I achieve the same?

B.: By preventing the mind from straying out after thoughts, desires and imagined objects of sensory perception.

Q.: If the world is a dream, am I making efforts to Realise the Self within a dream?

B.: Yes.

Q.: But there will always be other dreams! Do we have to make efforts to Realise within each and every dream?

B.: If effort is going on to Realise the Self within this dream, it means that the same effort is going on within all other dreams also.

Q.: Discussions, lectures and meditations: are they not useful for attaining Realisation?

B.: All these are only secondary aids, whereas the essential aid is Guru’s Grace.

Q: How long will it take for one to get Realisation?

B.: Why do you desire to know?

Q: To give me hope.

M.: Such a desire is also an obstacle. The Self is ever there, there is nothing without it. Be the Self and the desires and doubts will disappear. The Self is the witness in sleep, dream and waking states of existence. These states belong to the ego. The Self transcends the ego. Ego or no ego, the Self remains always. It is ever as It is. Did you not exist in sleep? Did you know then that you were asleep?Was there awareness of the world in sleep? In sleep you remained without a body and without a world. Why do you now hanker after these? In jagrat [watchfulness] you also remain aloof from body and world. It is only in jagrat that you describe the experience of sleep as being unawareness; therefore, the consciousness when asleep is the same as that when awake.

If you know what this waking consciousness is, you will know the consciousness that witnesses all the three states; such absolute consciousness is found by means of seeking the source of pure consciousness.

Q: In attempting to trace back pure consciousness to its source, I am overwhelmed by sleep and soon fall into slumber.

B.: No harm!

Q: I still maintain that to me sleep is nothing but a mere blank.

B.: For whom is the blank? Find out. You cannot deny your existence at any time. The Self is ever there and continues in all states.

Q: Should I remain as if in sleep and be watchful at the same time?

B.: Yes. Alert watchfulness is the true waking state. Therefore, the state of jagrat-sushupti [waking deep sleep] will not be one of sleep, but sleepless sleep.

If you go the way of your thoughts you will be carried away by them and you will find yourself in an endless maze.

Q: So, then, I must go back, tracing the source of thoughts.

B.: Quite so; in that way the thoughts will disappear and the Self alone will remain.

Q.: Does the practice ‘Who am I?’ lead to any spot inside the body?

B.: There is no inside or outside for the Self. These concepts are merely mental projections of the ego. The Self is pure and absolute. However, till Realisation is gained, it may be said that consciousness has a locus in the body, which is located on the right-hand side of the chest.

Q.: Is not intellect a help for Realisation?

B.: Yes, up to a certain stage. Even so, realise that the Self transcends the intellect; the latter must itself vanish in order that the Self might be Realised.

Q: Does my Realisation help others?

B.: Yes, certainly. It is the best help possible. However, the actual truth is that there are no others to be helped, for an Emancipated soul sees only the Self in everything, just like a goldsmith estimating the gold in various jewels sees gold and nothing but gold. When you identify yourself with the body, forms and shapes are to be found. But when you transcend your body the others in the world disappear along with your body-consciousness.

Q: Is it so with plants, trees, et cetera?

B.: Do they exist at all apart from the Self? Find out. You think that you see them. The thought is projected out from the mind. Find out from where the mind rises. Thoughts will cease to rise and the Self alone will remain.

Q: I understand theoretically. But thoughts refuse to subside.

B.: Thought is nothing but mental effervescence. Mind is only a bubble floating on the Self. Break the bubble and you are the ocean.

Q.: Is it the mind that creates the world we see?

B.: Yes. It is like a cinema show. There is the light on the screen and the shadows flitting across impress the audience as the enactment of some screenplay. If in the same screenplay an audience also is shown, what is the position? The seer and the seen will then only be the screen. Apply this analogy to yourself. You are the screen, the Self has created the ego, and the ego has its accretions of thoughtswhich are displayed as the world, the trees, plants, et cetera about which you are asking.

The truth is that all these are nothing but the Self. If you see the Self, the same will be found to be all, everywhere and always. Nothing but the Self exists.

Q: Yes, but I still understand only theoretically. Yet the answers are simple, beautiful and convincing.

B.: Even the thought, “I do not Realise.” is a hindrance. The Self alone IS and He alone could ever BE.

Q.: What are vasanas?

B.: Habits of thought, accumulated tendencies of mind, and intellectual proclivities.

Q.: How does one get rid of these hindrances?

B.: Seek the Self through meditation in this manner: trace every thought back to its point of origin, which is only the mind. Never allow thought to run on. If you do so, it will be unending. Take it back to its starting place — the mind’s essence of pure consciousness — again and again, and thought and thinker will both die of inaction eventually.

The mind only exists by reason of thought. Stop thought and there is no mind. As each doubt or depressing thought arises, ask yourself, “Who is it that doubts? What is it that is depressed?”. Go back constantly to the question, “Who or what is this thing called ‘I’? Where is the source of the mind?” Tear everything out and go on discarding until there is nothing but the Source of all left. And then live always in That and only in it.

There is no past or future, save in the mind. Only present exists. Yes, even the present is mere imagination. It IS. That is all. Ehyeh Asher Ehyeh. [I am that I am]

Q.: How can I help another with his or her problems and troubles?

B.: What is this talk of another? There is only the One. Try and realise there is no ‘I’ no ‘he’ no ‘you’, only the One Self which is all. If you believe in the problem of another, you are believing in something outside the Self. You will help him better by realising the oneness of everything than by any outward activity. The ego masks the Reality.

All mental activities during the states of jagrat and swapna [dream] are thehandiwork of the ego only. The emotions and intellect are merely mind-manufactured fictions. In deep sleep the body is lost, but yet the Self is there. It is the distracting, active mind that veils the real Self.

Q.: What meditation will help me?

B.: No meditation on any kind of object is helpful. You must learn to realise the subject and object as one. In meditating on an object, whether concrete or abstract, you are destroying the sense of oneness and creating duality.

Meditate on what you are in Reality. Try to realise that the body is not you, the emotions are not you, and the intellect is not you. When all these stand discarded you will find That.

Q.: What is ‘That’?

B.: You will discover it yourself. It is not for me to say what any individual experience ought to be. ‘That’ will reveal Itself to the mature aspirant automatically. When It does reveal Itself, hold on to It without ceasing.

Q.: I still maintain that in trying to still the mind, I am likely to fall asleep.

B.: It does not matter. Put yourself into the condition that is in deep sleep, but with awareness. Then watch yourself to ensure that no thought arises to disturb your peace. Be asleep consciously, instead of unconsciously. There will be then only one consciousness.

From that time onwards, I started a routine that was to be the same for many weeks. The rickety cart would turn up at six in the morning. It took me up to the ashram and came back again at seven-thirty in the evening for the return journey.

Up at the ashram I was given a small hut, seven feet by seven, for my use during the day. In it was a wooden plank, a chair and a table on which were a basin, towel and soap. Not luxurious, but the thought and care with which it had been provided touched me more than I can say.

There were two chief meals at the ashram, one at eleven-thirty in the morning and the other around eight in the evening. I ate with the others at the morning one. The food was more or less the same at both — rice, with an assortment of vegetables and milk curd. Everybody sat on the floor in front of an individual strip of banana leaf.

The question of food, especially the strict vegetarian meals that were served in the ashram and the diet prescribed conducive for the spiritual seeker by Bhagavan himself, was something a Caucasian would necessarily question. So I sought decisive clarification from the Master on this practice.

Q.: What diet is prescribed for a spiritual seeker?

B.: Sattvic food in limited quantities.

Q: What is sattvic food?

B.: Wheat, rice, vegetables, fruits, nuts, et cetera.

Q: Some brahmins take fish in Northern India. May it be done?

No answer was made by Bhagavan.

Q.: We Caucasians are accustomed to a particular diet; change of diet affects health and weakens the mind. Is it not necessary to keep up physical health?

B.: Quite necessary. The weaker the body the stronger the mind grows.

Q.: In the absence of our usual diet our health suffers, and the mind loses strength.

B.: What do you mean by strength of mind?

Q.: The power to eliminate worldly attachment.

B.: The quality of food influences the mind. The mind feeds on the food consumed.

Q.: Really! How can the Caucasian adjust himself to satvic food only?

B.: (Asking another Caucasian who was seated in the vicinity) You have been taking our food. Do you feel uncomfortable on that account?

The gentleman responded by saying that he was comfortable with the food served in the Ashram, owing to the fact that he was accustomed to it.

Q.: What about those not so accustomed?

B.: Habit is only adjustment to the environment. It is the mind that matters. The fact is that the mind has been trained to think of certain foods as being tasty and good.

The food material is to be had both in vegetarian and non-vegetarian diet equally well. But the mind desires flesh-food as it is accustomed to the same and considers it tasty.

Q.: Are there restrictions for the Emancipated soul in a similar manner?

B.: No. He is steady and not influenced by the food he takes.

Q.: Is not killing life to prepare meat-foods unethical?

B.: For the mumukshu [seeker], yes. Ahimsa [Non violence] stands foremost in the code of discipline for yogis.

Q.: But even plants have life.

B.: So too the slabs you sit on!

Q.: May we gradually get ourselves accustomed to vegetarian food?

B.: Yes. That is the way. Food affects the mind. Certain kinds make it more sattvic. For the practice of any kind of yoga, vegetarianism is absolutely necessary.

Q: Why do you take milk, but not eggs?

B.: The domesticated cows yield more milk than necessary for their calves, and they find it a pleasure to be relieved of the milk.

Q: But likewise the hen cannot contain her eggs!

B.: But there are potential lives in them.

Q.: Could one experience spiritual illumination whilst normally eating flesh foods?

B.: Provided you slowly wean yourself away from them and gradually accustom the body to purer types of food. But in any case, once you have attained Illumination, it will make little difference what you eat. It is the early stages that are important. On a great fire it is immaterial what fuel is heaped.

“Meditate on the Self, and on that alone. There is no other goal.”

The Maharshi’s philosophy and teaching is the purest form of Advaita, known as Ajata-Advaita.

As the days passed, I saw more and more clearly that this was no theoretical philosophy. He himself lived it continuously and joyously. He was one of the few I have met who were not only perpetually happy but also completely untroubled by the world.

Edited by John David Oct 2021

The Aghori Sadhu Life Story

Aham Sphurana

A Glimpse of Self Realisation

New Book about Sri Ramana Maharshi

Available Worldwide

On www.openskypress.com and Amazon:

“In my opinion, Aham Sphurana, a Glimpse of Self Realisation, will become a Treasure Trove of Wisdom to the Seekers of Truth in general, and particularly to the devotees of Bhagavan.”

Swami Hamsananda – Athithi Ashram, Tiruvannamalai

The Aghori Sadhu Life Story

Real Aghori Stories

A strange, decrepit old sadhu, who claims he is a centenarian, has arrived at the ashram. When asked for his name he gives the response, ‘Purampoekku chamiyar’. He claims to have first met Sai Baba in 1898; ever since leaving the saint, according to him, he has never lowered his right hand; it remains pointing up towards the sky, index finger unfolded and outstreched straight but the other fingers folded in. The arm seems covererd with greyish-white dust or fungus and the long fingernails have become an intertwined mass reaching down to the elbow.

There are lumps of knotted hemispherical flesh all over his body, particularly a large one above his eyebrows. His back is hunched and his legs severely bandied, so that his knees are splayed wide apart. He walks with left hand clutching his gyrating hip and right pointing at the sky. He assures B. that even whilst sleeping and attending to calls of nature, his arm is never lowered. As a parting gesture, Sai Baba had given him darshan of Shiva; as a mark of gratitude he has taken a solemn vow that he ought not toever lower his right hand. This is his guru-dakshina to Sai Baba. His body, and the single orange 4-cubit dhoti that is his only clothes, are smeared with holy ash.

The effect is particularly pronounced with regard to the face; blood-shot eyesstare out of a grey face decorated by a matted beard and hair reaching down till the knees. When not engaged in talking, he chants, without pausing to draw breath, in a mildly audible manner, ‘Shiva, Shiva, Shiva…’; the inflection of his intonation at uttering the incantation seems to be perforce characterised by manner of pleading thraldom. One cannot deny that there is an unpleasant odour emanating from him. He is cross-eyed to an extreme degree. It takes a while to discern that the colour of his bedraggled dhoti is the saffron; so soiled is it. His head droops down in perpetuity except when he is talking. He pays no heed to anyone else in the ashram; the only apple of his eye happens to be the master.

The sarvadhikari offered him new clothes, but he appears not to hear. He sat near the Sofa and told B. his story, how he had been born into an honourable Brahmin family in Conjeevaram and had developed proclivities toward licentious behaviour in early youth, as a result of which his family had been ostracized from the community. Unable to bear the anguish, his parents had committed suicide by hanging from a banyan tree. He still remembers the sight of his mother’s and father’s swollen face andbulging eyes. His father died quickly, but his mother took a long time, twitching and kicking in agony so that her garment became divested off her and fell to the ground as a consequence.

He could not move to cover her nude cadaver because the parents had tied him up whilst he had been sleeping under the tree with them. He had awakened to the sounds of his dying parents writhing from the tree. He cried and cried but he could not break free. Tears were dripping off his mother’s lifeless eyes, and trickled down the end of her pretty snub-nose [ லடச்ணமான seemed to look at him understandingly, pityingly even; those lovely eyes, once so remarkably charming and vivacious, were now glazed over with the coldness of brutal death. The memory of those eyes remain etched in his memory forever. He had relished in taking delight in nude, nubile bodies ofravishing young women; now he wanted to cover his mother’s nude cadaver, for this nudity nauseated him, but he could not; he found himself forced, by aperverse stream of inviolable attraction, to stare at the form inside which he had germinated, repulsed and fascinated at the same time by its present naked, grotesque condition.

Slowly a crowd began to gather at the place. Before anyone could talk to him, a mysterious sadhu appeared at the place, untied him and threw some sacred ash at his face. That was the last thing he remembered before he woke up at Benares. He stayed there with a group of cannibalistic Aghori sadhus whose exclusive diet was putrid human flesh and cows’ urine. The sadhus made money by manufacturing hooch; stirring the foaming, stiflingly pungent liquid, boiling away day and night in large copper urns, using human femurs as ladles, was the first task assigned to him. He participated in their strange rites and rituals, going to smashanas at midnight and dancing round and round burning bodies. In the dead of the night he co-operated in secretly ‘hijacking’ off cadavers left to float away in the Ganges. The bodies were brought to the secluded abode of the Aghoris and buried underground in a mixture of human excrement, boiled and smashed centipedes, and clayey soil.

A year later the bodies would be excavated, taken to pieces and consumed raw by the experienced Aghoris, and after boiling in anethole, acetic acid or methanol by the junior ones. None dared to come to their remote abode, situated by an isolated levee of the Ganges, except the man bringing them chemical supplies once a year. Occasional wayfarers would pass the place by with cloths draped over their noses. Theworkers in the smashana adjacent would not dare stay in the ghats after sunset. Sodomic pedication rituals were also practised by the Aghoris on every amavasya night by the light of candles lit inside skulls. After several years with the Aghoris, he was bathing in his usual abandoned spot on the Ganges one day, when a frightful paralytic stroke seized him and his legs and hands became petrified with numbness.

He was about to drown when a stout hand pulled him out of the water in a single swift movement and he found himself face to face with the enormous Trailanga Swami. The Swami commanded him to visit the great mystic Sri Ramakrishna. He replied he did not know where to find him. The huge Swami gave him an address located in a place called Cossipoure near Calcutta, and bade him memorise it; he also asked him to make his visit at the dead of the night. He complained he did not have the money to undertake the expedition. The Swami pinched his stomach hard and said, ‘O! Aghori, when you shall have your next bowel movement, search carefully and you will find that your needs have been taken care of.’.

So saying, he laughed and jumped into the Ganges, disappearing beneath theswallowing waters. Sure enough, the next day morning, he found a heavy gold coin in the manner predicted. Without informing his fellow Aghoris, he left for Bengal. Whilst on the train, he felt suddenly felt giddy and drank some water from a jar proffered unto him by a sufi-pir who was his co-passenger. He fell unconscious immediately. Just before losing consciousness, he heard the old moslem laughing and saying, ‘I am sorry, but Allah has decided that you must merge into Him in this lifetime.’. When he awoke he was at Howrah station, lying down on the platform. His appearance had become totally unrecognisable.

The skin all over his body had broken out into warts. He was a hunchback. He was unable to exercise any control over his bowel movements and was constantly passing motions involuntarily. His knees had splayed out in opposite directions. His hip would move in an ungainly manner whenever he attempted to walk. If he tried to walk too fast, he would fall down. He thrived on beggary at the station for a few days. Then he remembered Trailanga Swami’s advice and walked to Cossipoure. He waited outside the garden till it was well past midnight. Then he scaled the wall and somehow landed unhurt on the other side.

In the darkness he stumbled for a while blindly. Then a strange figure arrived with a diya, balanced on a copper plate, held in the left hand. The right hand was punctiliously cupped around the diya to prevent it from being extinguished by the vagaries of the wind. The man was thoroughly emaciated; he seemed to have sticks for limbs; and there was blood-soaked linen wrapped around his throat. Yet the eyes were live coals. Those eyes were enough to tell him who he was facing, that it was no mortal; they were nothing like he had ever seen. A strange, sweet voice spoke in an unheard-of tuongue. Yet he understood every word, although of the language itself he could not make head or tail. ‘My son…’ said the Paramahamsa, ‘why have you kept me waiting so long?’

The Aghori burst into tears and fell at the Paramahamsa’s feet and kissed them again and again. After some time the Paramahamsa said: ‘You are one of the 5 rarest of men destined to meet all the 3 Shooting-stars. Gowhauti is your next destination. Forthwith proceed to the temple of Kamakhya upon the Nilachala mountain. You should sit continuously in the sanctum sanctorum [garbagraham] of Tirpurasundari and think only ‘Shiva, Shiva, Shiva…’; no other thoughts must form in your mind; will you pay heed unto my words or not?’. The Ahgori begged the Paramahamsa to cure his disabled figure. The Paramahamsa said with tears in his eyes, ‘ My son, I can, but I shall not. The Mother wants you to be Absorbed in this lifetime. For that suffering is necesssary. You will stay in the temple until the call arrives from Sakorie.’

The Aghori begged and pleaded, but the Paramahamsa only said in a teary voice, ‘You may leave through the gate; the gurkha will not wake up ere your departure. You will board the train to Gowhauti a few hours hence. For this necessary purpose, the detestable thing called money is to be found by you in the usual detestable manner.’

The Aghori wanted to look at the divine face for the rest of Eternity, but the master blew at the diya. By the time the Aghori’s eyes adjusted to the sudden darkness, the master was nowhere to be found. The Aghori made his way toward the street-lamp burning outside and soon found himself outside the compound.

Soon he made his way to the temple in the strange land where could not understand anyone. He sat by Tripurasundari day and night. The priests tried to drive him away when it was time to lock up the chambers, but the Aghori would not budge. Contemptously, they bodily lifted him and threw him out forcibly. But mysteriously, the key got jammed in the lock and would not turn. Another lock was sent for at once, a new one. This effort also met with the same result. Eight more attempts were wasted. Finally the Aghori was offered an apology. He was given an engraved plank to sit on, inside the garbagraham. With him inside, the old lock worked perfectly well. So, during the nights the Aghori remained alone with Tripurasundari. During the day he was mobbed by people who babbled unintelligibly to him and poured milk and honey over his head. He had become to weak to protest or wash himself; so he just sat there. When he felt hungry he ran his palm over his head and then licked it. There he sat motionless as days passed into weeks, months and years, thinking only, ‘Shiva, Shiva, Shiva….’.

During the night Tripurasundari emerged from inside the sanctum sanctorum and danced with him in ecstasy. The dim light of the diyas lit by the priests at the time of their leaving made the dew-drop-like beads of sweat formed on Tripurasundari’s three breasts shimmer as she danced with him in the crazed joy of blissful divine Union. Sometimes thoughts of carnal craving formed in the Aghori’s mind as he touched the cool body of Tripurasundari. The moment this happened, she disappeared; in her place the Aghori’s dead mother appeared suspended from the ceiling by a ligature round her neck, exactly as he had seen her all those many years ago: the nude body, the tears dripping down the end of the capsicum-shaped nose, the bulging eyes staring with pitying compassion, but yet surely dead.

Then the Aghori screamed in agony and his lust was broken; Tripurasundarireturned and the dancing continued. She would tell him stories of aeons ago when the devas and asuras were at perpetual war; ultimately the Earth had fallen into the hands of the asuras; yet among the asuras there were God- fearing souls, deeply pious and wanting to adhere to dharma… He would address Her as ‘Amma’ and lie on her lap, while she told him many, many stories, lovingly stroking his grimy head… Passionately he would plead with her to kill him, saying that his life had reached a point of utter purposelessness, and that death by her honorable hand would grant him Salvation. She would smilingly shake her head. Two-and-a-half years passed thus in blind bliss. And then one night when the Aghori made his usual request to be killed by her hand, she replied to the plea for the first time; she pleaded her helplessness in the matter, saying cryptically, ‘Although I am a god and therefore have the Transcendental Consciousness, I cannot rescue you from samsara. Only a Guru can do this.

I am perceived by you; therefore the truth of my own reality is on a par with yours. Thus I cannot Liberate you. Only one who is here, but yet not, can take you away from here, which is not.’ The Aghori became deeply distressed upon hearing this, and screamed, ‘Who can be greater than you, Mother? Can anyone be greater than my mother, who is God Herself? Why do you deceive me thus, Mother?’. Tripurasundari placed her hand calmly upon the Aghori’s forehead and said plaintively, ‘Dear child, I am Yogamaya. I am the Empress Supreme of Illusion. It is within my competence to grant worldly wealth and riches, fame, power, physical invincibility or anything else on this plane of Maya. But what your soul craves for is Aathmavidya. That I have no power to grant. When the time comes, this certainly I shall do for you, for this alone I can possibly do to help you: I shall die for you so that you lose yourself in the Real.’

The Aghori went almost mad with the pain he felt upon hearing these words. Tripurasundari clasped the weeping, deformed child in her bosom and said, ‘My son, know this and accept it to be true: we are both unreal. You are seeing me. Thus I cannot be the Real God for whom your soul craves with such mad passion. I am the reason why God is hidden from you. The moment you become mature enough to learn to appreciate this fact and thus begin to despise me, I shall commit suicide, just like I did in the human form at Kanchi, to entice you to plunge into the Path. Then you will become blind to me, and God shall shine forth.’. But the Aghori could not make head or tail out of these words. He wept bitterly, ‘Do not leave me yet again mother…’. He began yelling, ‘Amma vaendum… Amma ennai vittu pogakkoodadhu… I do not want Salvation, just let me remain with you for ever and ever…’. Tripurasundari said: ‘I also want to remain with you.

But I cannot be selfish. I have a responsibility to deliver you up to the divine End. A few days later you will leave this place and entrain for Ahammadhnagar. From there walk to the village of Seeradi. Ask for the Masjid of Hakkim Sai. You may take this to be my last darshan.’. Upon having heard these words, the Aghori rushed to clasp the sword of the Mother from the diety in the garbagraham, for he wanted to end his life then and there. He seized

the sword but the Mother laughingly wrested it away from him with ease. ‘Do as you have been told, child.’. But the aghori held on to her blouse and would not let go. ‘Come what may, I shall not part from you.’, he said resolutely. The Mother merely said, ‘Partake of my ambrosia.’. So saying, she spread her legs and with them straddled an engraved pillar in the chamber. Fresh, sweet- smelling blood gushed forth and flowed in glistening serpentine rivulet.

The Aghori drank with joy to his heart’s content. So rapt was he in the act of licking the nourishing blood off the floor that he invoulantarily relinquished his grasp upon the blouse of the goddess. That very moment the goddess laughed and pounced into her stone idol, disappearing instantly. The Aghori let out an anguished cry, but that was the last he saw of Tripurasundari in the flesh. Forby begging and threatening in turns. But stone remained stone. Finally he took leave of the priests. They loaded him with presents and honoured him by presenting him with a pair of silver cymbals. He left the place, sold the cymbals for which he had no use, and proceeded to Ahammadhnagar, reaching by means of a train journey that was cramped but on that account gave his vexed mind some relief from its torturous agonies, for watching the man on the Clapham omnibus filled him with incredulous wonder: there seemed to be no restlessness or impatience, whatsoever, to Realise God in one’s incumbent lifetime!

What sort of strange creatures were these, talking about mundane things connected with the temporal corporeal existence! As if any of it would matter in the face of grim Death. After two days of incessant walking, he managed to reach Seeradi at last. When, after making the necessary inquiries, by means of resorting to successive bouts of largely unsuccessful hand-gestures, he entered the Masjid, he saw that an old man was sitting there smoking a chillum. He was clothed in a Kafni and a towel was tied atop his head. He was tending to a fire burning nearby. He did not notice the visitor; his back was turned to him. No one else was there. The Aghori took a few steps forward. The hakkim turned suddenly and stared straight into his eyes; they were the same eyes that he had encountered in Cossipoure; they transmitted the same magnetic charm that arrested the activities of the soul and the agitations of the mind!

The Aghori prostrated to the Hakkim on the hard earth of the masjid, and begged to be blessed by him. Hakkim Sai said, ‘This place is called Dvarakamaayi. Maayi says that you may stay here until Shiva reveals Himself to you.’. The Aghori was overjoyed and asked the Hakkim whether he should continue his repetition of Shiva’sname or adopt some other sadhana, so that he could avoid rebirth; this, for some reason, seemed to infuriate the Hakkim beyond measure and he shouted in a rage, ‘How dare you talk about sadhana after coming to Maayi!’. The Aghori became afraid that he had offended the Hakkim and shrank into a corner of the derelict-looking building. The Hakkim kept staring at him and the Aghori burst into tears. ‘Are you going to ask me to cure you of your bodily deformities?’, said the Hakkim. ‘Never, never!’, cried the Aghori, ‘Only rescue me from samsara, O! noble master.’.

‘You need not do any sadhana. Remain in Dvarakamaayi till this brick is one day broken.’ said the Hakkim, pointing to a large earthern brick by his side. So, the Aghori tried to serve the Hakkim in a devoted manner. But invariably the Hakkim would stubbornly rebuff the Aghori’s attempts to please him with his devout services. The Hakkim insisted that the Aghori stay away from the eyes of other devotees visiting the Masjid; he was driven away to a corner of the ramshackle, partly-sheltered terrace on the roof of the building. For weeks he stayed in this manner, lovingly peering at the Hakkim through a large crack in the masonry. Finally the Hakkim took pity at the Aghori; during night he was permitted to sleep in the hall. The Aghori learnt that people referred to him as Sai-maula.

To the Aghori’s great joy the master asked him one day to massage his legs. ‘I have allowed you this divine privilege. What will you give me in return?’, asked Sai-maula. ‘I am ready to lay down my life.’, said the Aghori. The master thereupon simply said, ‘Everyday you must light my chillum early in the morning and offer it to me.’ The Aghori thought it was a simple task and felt relieved for the fact that nothing more arduous had been demanded of him. Early next morning he came down and stood reverentially before Sai-maula. The master offered him one of his chillums, a tiny pebble and some cured weed. The Aghori tried to light the chillum from the dhuni briskly burning at the place night and day. Mysteriously, when he approached close to the flames, they faded and disappeared; but when he receded they seemed to roar into life again. Try as many times as he might, the result was the same always.

Sai-maula became impatient and screamed, ‘What! Are you incompetent at even this simple task?’. The Aghori tried availing of the tinder-box, but strangely, the tough flint- striker broke into pieces upon the first attempt. Sai-maula’s fury knew no bounds; he roared, ‘Will you light my chillum at once, or shall I banish you from Masjidmaayi this very instant, once and for all?’. The Aghori did not know what to do and began to weep like a child in fear. He thought of his Mother Tripurasundari; suddenly he was seized by an inspiration. With the utmost intensity of the prowess of concentration he could possibly muster, he recalled before his mind’s eye the image of his beloved mother, hanging lifelessly from the banyan tree beneath which he had seen her cadaver suspended; her nude lower body and dead yet compassionate eyes floated vividly in front of his mind.

He pushed the pebble into it, then stuffed the weed, and pressed the chillum hard against his umbilical-cavity, all the while keeping the image aforesaid intact in his mind. The weed burst into flame! As the Aghori handed the chillum to Sai-maula, the latter smiled and said, ‘In this manner you shall light my chillum early in the morning everyday; otherwise who will absorb your mountain-load of karmic accumulation?’. The Aghori complied without hesitation; from that day onward, the first thought in his mind, when he awoke every morning, was only that of Sai-maula, followed by that of the sorry cadaver of his dear mother. As summer came the heat of the sun on the terrace became unbearable. But the Aghori never complained. One night the master beckoned to him and gave him a cloth which was dyed in green. He bade him have it tied around his head always. The Aghori obeyed.

The next day onward, when the sun attacked him, he felt no heat at all, but cool and refreshed! If ever he accidentely disrobed himself of the green head-cloth, the sun would scorch him. He stayed with Sai-maula for many years, eventually being permitted to present himself in the hall during the day and to run errands for the master. Almost two decades passed; then the dreaded event happened. A devotee sweeping the hall had broken the brick Sai-maula always used as a pillow.

The master wailed inconsolably like a little child and announced to a shocked gathering that soon his tenure on the Earth would end; then he told the story of the brick and its significance: “My Guru is Venkusa of Saeloor. I stayed with my Guru for 12 years. I never did any japa or pooja. I did one thing only- I stared at my master’s face uninterruptedly for all those years. I forgot food, sleep and everything else. I forgot I had a body. I saw and remembered only the moon-like face of my Guru. Finally my Guru asked me to close my eyes. I did not want to do so, for I could not bear to stop gazing at his divine, lovely face. But I could not disobey my Guru. So, shedding tears of agony, I shut my eyelids for the first time in twelve years, after overcoming through great struggle the harsh difficulty of recollecting how to do so.

The moment my eyes closed, my Guru appeared in the right-hand-side of my chest. I was overjoyed. I could see him more clearly than I had done for these twelve years. Seated in the heart of my heart, the beloved master sweetly beckoned me to embrace Him. I eagerly plunged into the heart to hug my master, for whom I had infinite Love. As soon as my master’s embrace trapped me, I died, after thinking my last thought, ‘I joyously discover that only my master has always existed, me never.’. This body went into deep samadhi, and the face glowed like the sun. Seeing this, another, older devotee of the master, who had been serving him uninterruptedly for half a century, became jealous, for my face had betrayed to him that I had gained the knowledge of the imperishable Athman.

He seized the large brick that the master used as his feet-rest, and dropped it on my head. Had it met its mark, the brick would have killed this body. The master said kindly, ‘This boy will lead millions on the path of Truth. He must not die without the fruit of his Realisation being made available to the whole of humanity. Therefore I cannot allow this brick to complete its task.’. So saying he sprinkled water at the falling brick. The brick froze in mid-air. Seeing this miracle, the disciple who had hurled the brick got frightened and made himself scarce at once. Meanwhile this body woke upfrom samadhi and glimpsed the face of the master, but without identifying him with it.

This body saw my master but I was not there to see, for I had lost myself in him.

The master continued: ‘For 86400 nimishas [ ] this brick will remain thus. It cannot remain so forever, for it has been hurled by a person of considerable spiritual merit; thus it cannot go without effect. It has been thrown with the aim of killing one life; that life has yet many tasks to complete upon this Earth, which it cannot return to, so as to effect the completion; thus that life ought not to be killed. The only way is to offer my own life.’ Ignoring all pleas and tears from his disciples, including myself, who held on to his feet in desperation, he went and calmly sat under the brick suspended in mid-air. All tried to drag him away from the spot, but his body had gone into samadhi and would not budge. We held our palms in a protective intertwined manner above his head. But the effort was destined to be useless. On the expiry of the 86400th nimisha, the brick, which for years had supported the master’s feet, crashed down upon his neurocranium, easily tearing our hands away. His skull exploded open and the contents spattered and drenched the earth.

We were forced to bury him without the head. On learning that the master had given up his life for my sake, I went to the Manasarovar lake by foot to drown myself there. I tied the brick which had ended my Guru’s life securely to my feet, and jumped into the lake; but Mother Parvathi pulled me out by the hair and asked me, ‘Is this how you utilise the gift of elongated lifespan your Guru has given you by sacrificing his own life? Should you not carry out his vision for you?’. I felt ashamed of myself. Mother Parvathi said, ‘Go to Seeradi at once. From there you will bring Light and Joy into this dark world.’. Although I did not at all desire to play the role of a Guru, I bowed my head in assent, for I could not disrespect what evidently had been my Guru’s wishes. The Mother said, ‘Do not fret; take this brick with you as your Guru’s blessings; when it is broken the prarabdha of your body has ended.’

Then she gave me some jujubi fruit to eat and vanished. From there I automatically walked and walked without knowing where I was going. I carried this brick on my head everywhere as my Guru’s prasad. Eventually I arrived here. I stayed here for sometime. I buried my precious brick at the foot of the neem tree yonder. Then I went to fight at Gawlioure against the Caucasian invader. We lost and the cunning Englishman won. I narrowly escaped capture. Then I returned here. After I settled at this Masjid I remembered and searched for my brick under the neem tree, but someone had removed it. The absence of the brick puzzled me; I wondered whether there was any culpability by way of negligence on my part as a result of which my Guru’s prasad I had come to be forced to forfeit; I felt as though I had lost my Guru once again.

I asked the sun, the moon, the wind, the oceans, the rivers, the sky and the birds whether any of them had seen my brick. Nobody gave me a satisfactory answer. Then I asked all the mountains of the Earth. I exhausted all mountains but one: the mountain of Shonadhri. When, with the intention of communicating with the mountain, so as to question it regarding the whereabouts of my invaluably sacrosanctious brick, I turned my mind towards it, I became lost in a deep samadhi. So great was the effulgence of Poorna-jnana radiating from out of the mountain that, for a time, I forgot even my Guru’s name. Those who then came to the Masjid thought I was dead and made arrangements to bury my body on the outskirts of the village. At the time I was wearing an amulet upon my neck. With the words, ‘Keep this carefully. It is forged from metal that fell as a fiery ball into the Earth, from outer space, nearly 4500 years ago, and it contains a portion of the umbilical-cord that was instrumental in bringing into this world Moosa, the Prohpet of the people of Alsham.’

Abdulaziz Binmuhamad Albashir, the fakir who introduced me to the blessed feet of my Guru Venkusa, had given it to me as a parting gift before transferring custody of me over to my master.

The men carrying out my interment thought it a waste to allow the amulet to be buried also; they were under the impression that it was made out of silver. They ripped it away from my neck; at that moment I awoke from my long samadhi. The men ran away terrified, but my amulet was gone. Now I had lost everything; but apparent happenings on the physical plane were no more wont to affect me after my dissolution in my Guru. I came back to the Masjid and plunged into samadhi again. The body became weak and shrunken with the passage of time; I had no interest in sustaining or prolonging life in the bodily existence.

Visitors were saddened by my plight but none dared to attempt to rouse me. One day, Mhalsapati came rushing into the Masjid. He was carrying the brick in hand; he had had a dream in which he had been asked by Khandoba to dig at a particular spot by the side of the banyan tree appurtenant to the premises of the temple; he had also been asked to deliver up the brick found there to the Masjid of Sai-maula. I was happy to receive the brick, my life-companion ever since that day. I thought of giving Mhalsapati some reward for having reunited me with my Guru’s prasad, but could not find anything suitable. Just at that moment a crow flew into the Masjid and dropped something on my lap from its beak: it was the fakir’s amulet.

I gladly gifted away the amulet to Mhalsapati. Everyday I lie down with this brick supporting my head. Today this brick has broken. It means that my prarabdha has broken. I cannot survive the destruction of my beloved companion. I cannot survive the breaking of this brick. Soon I shall be taking leave.” The Aghori was shedding tears of immense agony as he heard these words. That night Sai-maula commanded him to look into his eyes. The Aghori was startled to suddenly see Shiva in the place where Sai-maula had been. Shiva danced round and round the dhuni, rattling this damaru ferociously for all the world to hear. He beckoned the Aghori to come close, but the latter stood rooted to the spot in terror. Shiva raised his right hand up towards the sky, pointing at the heavens with his index finger. The Aghori extemporaneously mimicked the gesture, without knowing why he was doing so. Then Shiva laughed and opened the vertical eye on his forehead. As soon as the Aghori, timorous yet fascinated, stared into that unfathomable eye, he lost consciousness of the physical world.

The next thing he remembered was that Sai-maula was sprinkling him with water. Sai-maula commanded him to get up and told him that his work here was finished. The Aghori fell at Sai- maula’s feet and washed them with tears of gratitude and joy for having shown Shiva to him. Sai-maula merely glared at him as he ususally did. Then he produced a silver-coin from his robes and asked the Aghori to go to Swami Nigamananda; the Aghori was bade listen to the address and commanded to start forthwith. The Aghori had not the courage to naysay the word of the master. He quietly departed after prostrating once more at the feet of the master. After walking a few steps away from the Masjid, the Aghori became aware that his right hand was still poised pointing up in the air towards the stars and the moon. Out of the Love, respect and gratitude he bore toward Sai-maula, he resolved to let it be so always.

Swami Nigamananda gladly received him and day after day taught the Aghori the nuances of Aathma- vidya. The Aghori asked the master to impart unto him knowledge of the ineradicable Parabrahman. The master responded with the kind words, ‘My child, you are older than me in years. You have suffered much in God’s name. You are a worshipper of Shakthi. Yet, to reach the Absolute, which is at once both intimate and remote, you must learn to disconnect your mind from the senses; so far your experience of God has been in the objective realm only; this is woefully inadequate for Liberation, my son. You must practise retaining the mind in the pure essence of its nature, which is sath; this sadhana alone can facilitate you to realise God in the subjective realm; such experience of God alone is real and intransient.’.

He was also told that according to the teachings of the Upanishads, Gaudapada, and Shankara, the one sole Athman alone was real and the world unreal; experiencing the Athman was possible only if one’s belief in the reality of the objective world was given up. On account of the master’s benevolent, vigilant guidance, and as a result of years of rigourous training, the Aghori finally experienced Brahman through nirvikalpa samadhi, just weeks before the master gave up the body; after three days he awoke from samadhi and proudly announced to the master that he had won Liberation by the latter’s redeeming grace; the master made no response. Last year, however, only a few days before his final absorption in the Infinite, the master called the Aghori by his side and told hm, ‘Do not be filled with conceit and think that you have reached the final state of Liberation. You have not.’ The shocked Aghori could not think of any reply to make. The master told him, ‘After this body dies, go to your home-town of Kanchi. Meet the Sankaracharya who is the pontiff of the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetam. Obtain his blessings. He will show you the way to the Guru who will bring about your Liberation.’

After Swami Nigamananda passed away, the Aghori obediently

did as he was told. When he arrived at his destination, he was not permitted to go inside the Peetam. He tried to stealthily make his way in during the night, but was captured, severely beaten, and thrown out. He lived on the road near the Ekambaranathar temple, seated alongside the beggars outside the temple. Many people cast him curious glances because of his eccentric appearance. When the beggars were being fed, the Aghori ate with his left hand as was his usual custom. The organiser of the annadhanam consideredit disgraceful since there seemed to be nothing wrong with the man’s other hand. When the Aghori was asked whether the right hand was paralysed in its raised position, he replied in the negative.

The organiser asked the Aghori to eat with the right hand, saying that otherwise it would amount to insult of God’s prasad. The Aghori ignored him and went on eating with the left hand. The priests of the temple then arrived and told the organiser, ‘He seems to be a sorcerer who has come to this place with the express malefic intention of ruining all the good-merit[punyam] you are accquiring from sponsoring this annadhanam. Chase him away at once; otherwise, the entire punyam you are earning from this noble exercise of feeding poor people will fail to fructify.’

The Aghori was asked to get up and go away. He paid no heed since this was the first meal he was having in days, and he was desperate to wash his stomach with something. Then the organiser lost his temper. He brought some workers, and they bodily lifted him from the ground and threw him into the nearby gutter. There was an iron pipe-line running alongside the inner wall of the gutter. The Aghori’s forehead rammed against the same and the concussion caused him to lose consciousness. When he stirred it was the dead of the night and the place was deserted. He satisfied his hunger by means of licking leftover food off used banana leaves, a huge pile of which he found discarded nearby. Then, not knowing how to execute his mission of meeting the Paramacharyal, he lay down in a corner of the dusty road bemoaning the fact of his perverse fate to himself. Then he observed people were erecting a pandal and preparing a dais near the Kamakshiamman temple. He overheard a conversation between an elderly brahmin couple passing upon the road, and learnt that the Paramacharyal would come there in a few hours, at the break of dawn, to deliver a lecture.

In the darkness, he quietly crept beneath the dias when the workers were busily engaged in attending to some other aspect of the preparations. His spine ached from having to lie in cramped fashion beneath the low dias. He waited for hours before he finally heard a noisy commotion admist the gathered crowds; this meant that the Paramacharyal had arrived. In a flash the Aghori pounced from beneath the dais, fell flat before the Paramacharyal, caught hold of his feet, pressed his forehead upon them, and shouted, ‘Salvify me!’. The Paramacharyal’s attendants dragged him away at once and tried to restrain him from attempting to approach once more; when he seemed reluctant to give up his endeavor to again approach the saint, they tried to thrash him. The Aghori looked pleadingly into the eyes of the Paramacharyal; immediately the saint screamed, ‘Nirutthungoeda! Nirutthungoeda!’. The saint emphatically asseverated that the man ought to be fed and brought into his presence in the evening.

Reluctantly the order was complied with. In the evening the Aghori sat in padmasana before the saint and closed his eyes. He could feel his Ajna chakra vibrating and humming. Suddenly the saint touched the Aghori’s head with his stick. The Aghori’s body shuddered violently and he went into samadhi. He had no idea how much time passed thus. He awoke to water being sprinkled upon his person. The Paramacharyal was sitting opposite him, on the floor! The Aghori immediately prostrated to him. Of his own accord, the Paramacharyal said, ‘Your Moksha-guru is a perfected being whose residence is the sthalam which bestows Liberation when merely thought of. Go to Thiruvannamalai. Ask for Sri Ramana Maharshi.’. The saint then arranged for food and some money to be given unto the Aghori.

When the Aghori landed at the railway station here, he stood gazing in wonder at the beauty of the Arunachala mountain for a long time; for reasons unbeknownst to him this mountain elicited a feeling of awe from him. A couple of workers were removing luggage from a bogey and he was standing in their way inadvertantly. They called out to him repeatedly to move aside but he did not hear their words, so rapt was he in beholding the mysterious, picturesque pulchritude of the Hill. One of the men pushed him aside and said, ‘ ேடய் இ name indeed suited him very well, and therefore decided to adopt it for himself, as his monastic name. He went to the temple and had darshan of Lord Arunachaleshwara. Then he went for giripradakshinam. He spent the night sleeping in the forested region near simha-theertham. This morning he completed the girivalam and had darshan of Lord Arunachaleshwara again. When he set eyes upon the lingam, it emanated a reddish glow that was not visible to anyone else. Overjoyed, the Aghori has rushed straight to the ashram to tell his story.

Now he is before Bhagawan. Bhagawan’s eyes remind him of Ramakrishna’s, Sai-maula’s and Tripurasundari’s eyes. He feels Bhagavan’s cool glance of Grace penetrating his mind and flooding it with serenity and peace. He begs Bhagawan for Moksha.

B.: The responsibility to Salvify [bring about liberation from samsara] you is that of the Lord’s. You need not bother about it. Did you not surrender your life to God long ago? Why then do you bother about your Salvation? Having surrendered, one need not and ought not to harbour any cares or worries.

Your responsibilities are now God’s. Leave it to him to execute them as he sees fit, by using you as a mere tool. Do not identify with the body and imagine yourself to be the doer of its actions; if the ego is given up the body’s activities are found to go on of their own accord. You have no role to play in securing your own Liberation; or, your only role is to keep quiet. Just keep quiet. Bhagavan will do the rest.

Bhagavan seemed to treat the aged aghori with great compassion and solicitude. The Aghori was in turn peering with great joy into the master’s inscrutable eyes. It was now well after night-fall. The Aghori was given some food and then led by the sarvadhikari to Palakoththu, although the former asked that no trouble need be taken for finding him accomodation, for he was quite acclimatised to staying in the wild, and found staying admist civilisation strenuously burdensome.

Edited by John David Oct 2021

Aham Sphurana

A Glimpse of Self Realisation

New Book about Sri Ramana Maharshi

Available Worldwide

On www.openskypress.com and Amazon:

“In my opinion, Aham Sphurana, a Glimpse of Self Realisation, will become a Treasure Trove of Wisdom to the Seekers of Truth in general, and particularly to the devotees of Bhagavan.”

Swami Hamsananda – Athithi Ashram, Tiruvannamalai

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.